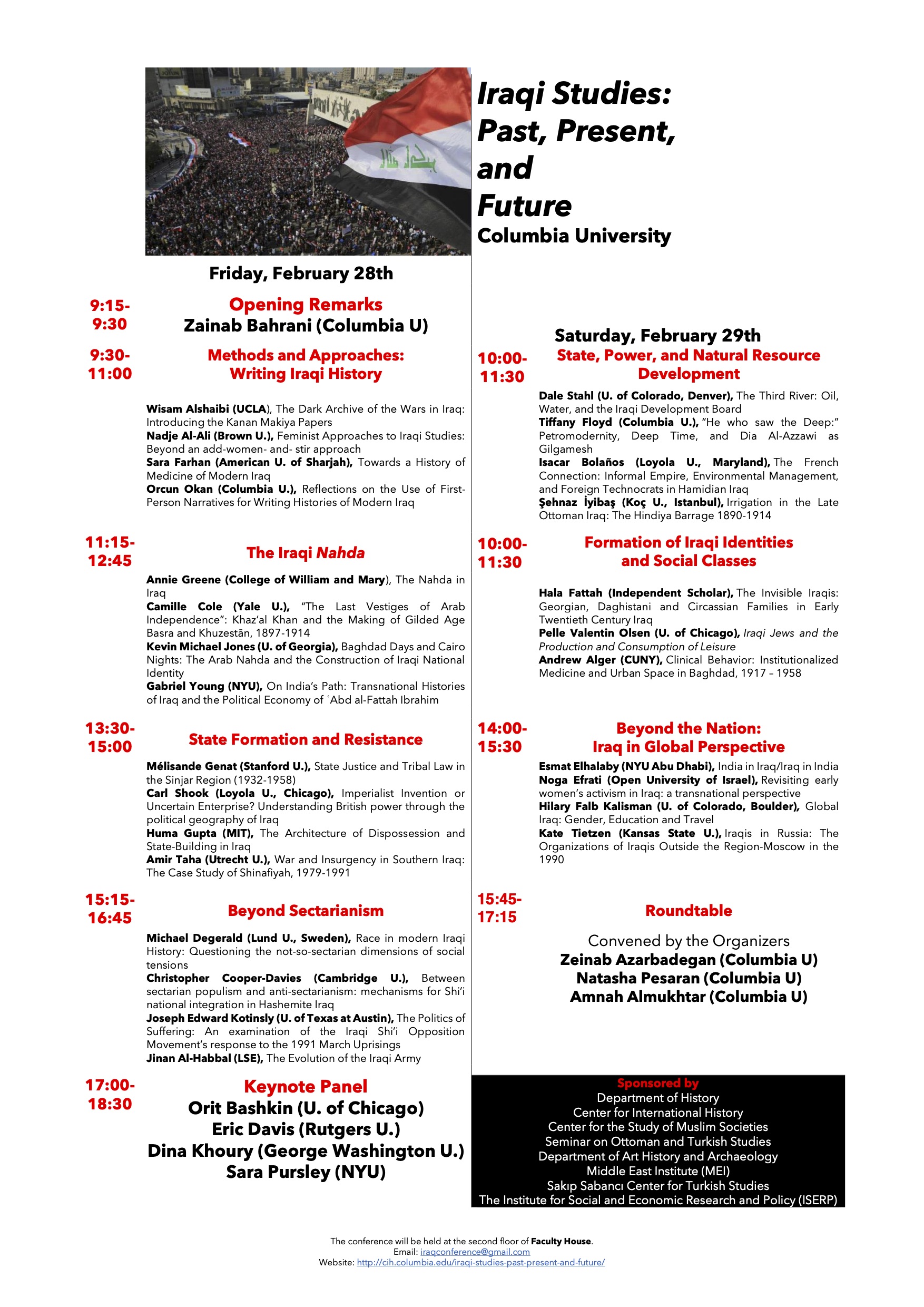

Iraqi Studies: Past, Present, and Future

28-29 February 2020

2nd Floor, Faculty House

Columbia University

This two-day conference brings together a diverse group of established and emerging scholars working on the history of modern Iraq from the Ottoman period to the present to interrogate Iraqi studies; taking stock of its past, reflecting on the present, and looking towards its future. Studies of modern Iraq have grown qualitatively and quantitatively in recent years. There is now a critical mass of innovative scholars in the US, Europe, and the Middle East who work on Iraq and are exploring new lines of inquiry in a number of different directions. It is common to see Iraq-themed panels and round tables at international conferences. Given this volume of scholarly activity connected to modern Iraq, it is an opportune time to critically reflect on and examine Iraqi studies and its status as a burgeoning sub-field of Middle East Studies.

We aim to discuss research trends, to identify promising new questions and sources, to exchange experiences and insights, and to encourage networking across period-specializations and field boundaries. Each panel will comprise a discussant and several speakers. A keynote panel of senior scholars will critically reflect on the state of Iraqi studies. Confirmed speakers for the Keynote Panel: Dr. Dina Khoury (George Washington University); Dr. Orit Bashkin (University of Chicago); Dr. Eric Davis (Rutgers University); Dr. Sara Pursley (New York University).

Among the questions we seek to explore are: How do we define Iraqi studies? What various methodological approaches inform our study of Iraq? Is Iraqi studies an inherently nationalist endeavor? How do different frameworks support or break with nationalist conventions? How has Iraq’s recent turbulent history affected how scholars access sources to study the country, its geography, its people, its history, its literature, etc.? How can we move past the sectarian and ethnic narratives of understanding the Iraqi past and present?

Organisers:

Zeinab Azarbadegan (Columbia University)

Amnah Almukhtar (Columbia University)

Natasha Pesaran (Columbia University)

Sponsors:

Department of History

Center for International History

Center for the Study of Muslim Societies

Seminar on Ottoman and Turkish Studies

Department of Art History and Archaeology

Middle East Institute (MEI)

Sakıp Sabancı Center for Turkish Studies

The Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy (ISERP)

In order to attend and to be added to our mailing list for updates related to the conference, please register here

Friday: 9.30-11.00 Panel 1: Methods and Approaches: Writing Iraqi History

Wisam Alshaibi, Weaponizing Iraq’s Archives

When the contents of an archive are closed to the public and scholars for security concerns, the collection is labeled as being “dark.” The Kanan Makiya Papers held at the Hoover Institution is one such collection. In my previous work, I have examined how the Kanan Makiya Papers—the collection of personal papers from the Iraqi intellectual and close advisor to the second Bush administration—sheds light on the uses of atrocities to build the case for war in Iraq. I now want to change course and examine how this collection of documents helps us understand how an exiled opposition movement endeavors to overthrow its home regime from abroad. The presentation will showcase material from the Kanan Makiya Papers which intimately details the close working relationship between the Iraqi National Congress and American political figures between 1991-2003. I will also discuss the legal challenges I have recently been facing due to my possession of Makiya’s documents and the research I am conducting with these files.

Wisam Alshaibi is a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology at UCLA. His dissertation examines the role of various Iraqi opposition movements in building the case for the United States’ invasion and occupation of Iraq. He uses this case to investigate broader questions about the role of experts in wartime, the instrumental use of human rights, and the micro-politics of political violence.

Nadje Al-Ali, Feminist Approaches to Iraqi Studies: Beyond an add-women- and- stir approach

This paper will provide a feminist critique of the prevailing gender blindness in much of the scholarship on Iraq. This is despite the fact that Iraq is an example par excellence of the intimate links between the politics of gender and changing political regimes at local, regional, national and international levels. Iraqi women, their bodies and sexuality as well as wider gender norms and relations, including contestations of masculinities, have been at the centre of political conflict and power struggles in post-invasion Iraq. The increase in authoritarian and more sectarian governance structures and patterns has gone hand in hand with more socially conservative, repressive and coercive gender politics.

Gender issues have taken centre stage in political and media debates in post-invasion Iraq. In fact, questions around women’s legal rights, their political representation as well as gender-based and domestic violence have constituted symbolic markers of difference between the old Ba‘th regime and new forms of governance in central and southern Iraq on the one hand, and the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) in northern Iraq on the other. At the same time, contestations around gender have also been at the heart of ethnic and sectarian tensions and conflict.

This paper has grown out of my academic research and activist work in relation to Iraq over the past 25 years. While addressing the frequent gender blindness in historical, sociological and political analysis of Iraq, my paper will also engage with the question of how to combine feminist scholarship and activism. How do we as scholars invested in Iraq personally and politically engage in scholarship that is academically rigorous and cutting edge while also being relevant and resonant with every-day life experiences and political realities on the ground in Iraq as well as within activist struggles in the diaspora?

Nadje Al-Ali is Robert Family Professor of International Studies and Professor of Anthropology and Middle East Studies at Brown University. Her main research interests revolve around feminist activism and gendered mobilization, mainly with reference to Iraq, Egypt, Lebanon, Turkey and the Kurdish political movement. Her publications include What kind of Liberation? Women and the Occupation of Iraq (2009, University of California Press, co-authored with Nicola Pratt); Women and War in the Middle East: Transnational Perspectives (Zed Books, 2009, co-edited with Nicola Pratt); Iraqi Women: Untold Stories from 1948 to the Present (2007, Zed Books), and Gender, Governance & Islam (University of Edinburgh Press, 2019, (coedited with Deniz Kandiyoti and Kathryn Spellman Poots).

Sara Farhan, Towards a History of Medicine of Modern Iraq

What can the history of medicine tell us about the nature of rule and the politics of identities in modern Iraq? And how did medical theories of disease and healing shape ideas about the centre and periphery, population control, bodies, and ethno-religious differences in the imaginations of nationhood? This paper presents a case for how the history of medicine in modern Iraq can provide us with a birds-eye-view on the one hand, and a microscopic perspective on the other, of the complexity, richness, and inter-connectivity of the social, cultural, and political dynamics that shaped modern Iraq. I argue that the history of medicine is an important category of analysis that can be used to examine the minutia while framing the grand narratives that make up modern Iraq’s history. Specifically, Iraq has a place in the history of medicine and its development that position it right in the centre of a transnational conversation. History of medicine also provides us with an intimate perspective of the way in which medicine was articulated, practiced, negotiated, and regulated in Iraq and by its inhabitants.

Disease, contagions, and eradication, professionalization, medical labour, and patient – care provider interactions highlight the diversity and complex inter and intra-communal interactions that fashioned Iraq’s society. It also highlights the unique local features that contributed to the transcription of specific approaches to medicine and public health policies, while at the same time underscores the commonalities the country shares with other regions around the world. Moreover, this category of analysis showcases the unwavering agency Iraqis possessed in these processes. This paper concludes by highlighting the plethora of scientific journals, many of which are in English, available to us to include in our classrooms and research. These sources are accessible through most academic search engines and databases. Ultimately, the history of medicine of modern Iraq conveys the complexity and richness of the country’s past all while transcending the sectarian and totalitarian narratives that have plagued the field.

Sara Farhan is an assistant professor of history at the American University of Sharjah, UAE and the Michael Elias DeBakey History of Medicine Fellow at the National Library of Medicine, USA. In August 2019, Farhan defended her dissertation “The Making of Iraqi Doctors: Reproduction in Medical Education in Monarchic Iraq, 1869-1959” at York University, Toronto, Canada. Her work explores the process of professionalization of medicine, and the medicalization of society in modern Iraq.

Orcun Okan, Reflections on the Use of First-Person Narratives for Writing Histories of Modern Iraq

First-person narratives on the past (in various forms including memoirs, autobiographical recollections and recorded public speeches) are crucial historical sources for studying modern Iraq. After explaining why that is the case with a focus on the period from 1914 to 1939, this paper makes suggestions as to what could be particularly promising approaches to these sources in “Iraqi studies.” The paper incorporates examples from (published) first-person narratives by prominent Iraqi statesmen — such as Naji Shawkat, Taha al-Hashimi, Jafar al-Askari and Nuri as-Said — as well as (unpublished) first-person narratives in the form of petitions written by a diverse group of Iraqis in the 1920s in order to find solutions to specific administrative problems of the day. The paper demonstrates that narratives by ex-Ottoman Iraqi statesmen can be highly useful for emphasizing the multilayered and multifaceted identities of these statesmen. This emphasis is crucial for questioning nationalist assumptions about what “Iraq” and being “Iraqi” meant at different times in history. However, the paper also stresses that historians must see beyond narratives by pivotal political figures in order to grasp the wide range of social dynamics which shaped the construction of Iraq after the Ottoman demise. New findings at archives outside Iraq can facilitate analyses of the agency exercised by historical actors whose experiences can shed new light on the making of modern Iraq. These analyses, in turn, can help historians challenge and move beyond elitist and gender-biased perspectives. In raising these points, the paper aims to contribute to particular scholarly debates among historians of Iraq — such as the one on the use of the term “Effendiyya” — as well as to the large and growing literature on the transition in Iraq from the Ottoman period to the British Mandate.

Orçun Okan is a Ph.D. candidate in the History Department at Columbia University. The MA theses he completed at Boğaziçi University in 2013 and at Columbia University in 2015 are titled “The Intermediate Generation: Ex-Ottoman Arab Leaders of Interwar Syria and Iraq” and “Politics of Remembering Midhat Pasha: Post-Ottoman Contexts of a Contested Memory in Turkey and the Arab East,“ respectively. The dissertation he hopes to complete at Columbia this semester is titled “Coping with Transitions: The Connected Construction of Turkey, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq (1918-1928).

Friday: 11.15-12.45 Panel 2: The Iraqi Nahda

Annie Greene, The Nahda in Iraq

The Nahda (Arab revival) has long been associated with interrogating Arab modernity and creating cultural production in the Arab cities of the Eastern Mediterranean. Yet, Iraqi cities have been ignored in studies of the Nahda, and Iraqi historiography has ignored the Nahda, relying instead on imperial and nation-based periodizations. I argue for the inclusion of Iraqi intellectuals in the narrative of the Nahda and the integration of the Nahda narrative in the study of Iraq. This paper, in emphasizing the connectivities of Ottoman-Iraqi cultural intellectuals, demonstrates the circulating ideas of the Nahda to the Iraqi provinces and from the Iraqi provinces in print during the late-Ottoman Empire, a phenomenon continuing through the establishment of the Hashemite Monarchy. I illustrate the active participation of Ottoman-Iraqi intellectuals to the Nahda through Arabic press networks, publishing poetry and prose in journals outside of Iraq. Furthermore, in recognizing language at the heart of cultural production, and the Arabic language at the heart of the Nahda, this paper questions the “language purity test” carried out by many of the intellectuals. In a multilingual empire with multiple cultural revivals–the Nahda’s being just one–what was the role of heteroglossia and bilingual individuals who were influenced by the Nahda? In light of this line of questioning, this paper frames the Nahda in Iraq as heteroglossic, and to illustrate this point, I examine Nahdawi ideas filtered through a colloquial Arabic, printed in the Hebrew script.

Annie Greene is a visiting Assistant Professor of Middle East history at the College of William and Mary. She received her PhD from the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago. She has held a research fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania’s Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies.

Camille Cole, “The Last Vestiges of Arab Independence”: Khaz‘al Khan and the Making of Gilded Age Basra and Khuzestān, 1897-1914

Khaz‘al Khan, shaykh of Muhammara (Khorramshahr) in the Iranian province of Khuzestan, was not an Ottoman, did not live in Iraq, and had no aspirations to either. This paper argues, however, that Khaz‘al’s accumulation of substantial date plantations on both sides of the Ottoman-Qajar border helped make the border tangible, while also underpinning a new imagination of the northern Gulf as a political space. Although this vision was not realized, exploring how it came to be forces us to expand our understanding of who and what made Iraq.

The paper sketches Khaz‘al’s approach to wealth accumulation, which depended on a legal embrace of Qajar subjecthood on both sides of the border. Khaz‘al managed the estates, which remained ecologically and socially linked, from his Fayliya palace south of Basra. The palace became the hub of a social and political scene which underpinned elite movements for autonomy and regional federation. While historians have largely attributed these movements to the work of Iraqis like Sayyid Talib in Basra, I situate Talib’s activism in the context of his relationship with Khaz‘al and their shared social circle. Beyond the Gulf, nahda thinkers and Islamic modernists from Syria and Egypt, observing the cultural and economic efflorescence of Fayliya, portrayed Khaz‘al as the ideal leader of the Gulf, in the vanguard of Arab-Ottoman renewal. In contrast to standard portrayals of the region as a backwater before the upheavals of oil, these nahda visions positioned Khaz‘al, and southern Iraq, at the center of geographies which are simultaneously familiar and unfamiliar. By centering my analysis on Khaz‘al and considering how his transborder estates engaged intellectual and cultural networks spanning Basra, the Gulf, and the wider Arab world, I argue for an approach to Iraqi studies that looks beyond historical and methodological borders to understand how those borders were made.”

Camille Cole is a PhD candidate in History at Yale University. Her dissertation uses microhistory to explore the history of land, law, and capital in late Ottoman Basra, focusing on how wealthy landowners and tax farmers used the tools and vocabularies of the modern state to accumulate land. She has published work on late Ottoman Iraq in Middle Eastern Studies and the Journal of Social History.

Kevin Jones, Baghdad Days and Cairo Nights: The Arab Nahda and the Construction of Iraqi National Identity

This paper addresses Iraqi contributions to the Arab Nahda and the evolution of Iraqi national identity in the late Ottoman era. The paper is derived in part from my forthcoming book about poetry, politics, and protest in modern Iraq. The first chapter of that book advances the argument that Iraqi contributions to the seminal Egyptian and Levantine periodicals of the late Ottoman period shaped both Iraqi and non-Iraqi conceptions of a distinctively Iraqi cultural and national identity. This paper expands on that argument in two ways. First, I broaden the scope of inquiry beyond poetry to include the prose debates about Iraq in journals like al-Hilal, al-Muqtataf, al-Muqtabas, al-ʿIrfan, and many others. Second, the analytical lens of the paper moves beyond historical narrative to more directly interrogate broader historiographical debates in Iraqi studies.

The paper engages directly with several of the key questions posed by the conference organizers. It grapples with the question of whether Iraqi studies constitutes an “inherently nationalist endeavor” and considers how the pan-Shiʿi loyalties of Najafi intellectuals and pan-Arab and pan-Islamic inclinations of certain Baghdadi intellectuals might undermine the “nationalist conventions” of the field. It also contributes a new understanding of the relationship between cultural production and national identity during the Arab Nahda by showing how the reception of Iraqi intellectual and cultural production in Egypt and Syria contributed to new conceptions of Iraqi national identity.

Kevin Jones is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Georgia. He earned his PhD in History from the University of Michigan in 2013 and served as Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at the George Washington University Institute for Middle East Studies in 2013-2014 before accepting his current position at the University of Georgia. He has published two articles about Iraqi cultural history and Middle Eastern labor history in Social History. His forthcoming back on poetry and the cultural politics of anticolonialism and national liberation in modern Iraq (The Dangers of Poetry: Culture, Politics, and Modernity in Iraq) will be published by Stanford University Press in Fall 2020.

Gabriel Young, On India’s Path: Transnational Histories of Iraq and the Political Economy of ʿAbd al-Fattah Ibrahim

How do we write histories of Iraq that neither presume it to be an “artificial state,” nor take the nation-state for granted as the premise and telos of politics? This paper suggests that one possible method is studying the transnational processes that have helped produce Iraqi national space as a historically specific form of political-economic organization. It briefly describes how my own research on Basra and southern Iraq between the 1920s and 1960s pursues this method by examining the infrastructural, commercial, and political circuits that connected this borderland city to the rest of the Persian Gulf world. Scholarship on the Gulf has generally ignored Basra and Iraq more generally, but my dissertation aims to show how Iraqi national space was partly forged through the same processes that reshaped the wider Gulf political economy in the mid-twentieth century, including oil production, labor migration, imperial realignment, and the formation of national states and citizen-subjects.

My paper attempts to justify this transnational approach by looking to Iraqi intellectual production from the interwar period. Specifically, I discuss the 1932 work of historical political economy ʿAla tariq al-hind (“On the Route to India”) by the Iraqi Marxist ʿAbd al-Fattah Ibrahim. In this text Ibrahim sought to understand the social and political conditions of Mandate-era Iraq by looking to the experience of colonial-capitalist development in modern India. Ibrahim saw in his historical present both past echoes and contemporary reverberations of the transformations that imperial and capitalist competition had wrought in India over several centuries. India was not only a historical reference point for Ibrahim but also a contemporary node in uneven, crisis-ridden formations of capital and empire; and the global interwar struggle against both. This paper therefore attempts to use intellectual history as the basis for mounting larger methodological critiques relevant to Iraq studies and beyond.

Gabriel Young is a Ph.D. student in History and Middle Eastern Studies at New York University. His prospective dissertation will explore the relationship between urbanization, state formation, and transnational political economy in the Persian Gulf, with a focus on Basra and the borderlands of southern Iraq between approximately the 1920s and 1960s.

Friday: 13.30-15.00 Panel 3: State Formation and Resistance

Mélisande Genat, State Justice and Tribal Law in the Sinjar Region (1932-1958)

This paper presents a case study of interrelations between state justice and tribal customary law. It uses the ‘tribal files’ of the Iraqi Ministry of Interior – housed at the National Library in Baghdad – on the Sinjar region in northern Iraq. They cover the period from 1932 to 1958, and fall within the framework of the Tribal Criminal and Civil Disputes Regulation (TCCDR) introduced by the British administration in 1916.

These files show a high degree of adaptability, cooperation and mutual understanding between the Iraqi central administration (under British influence) and the various tribal subjects. It is at odds with the protracted political tensions in Iraq described in the historiography. Revolts and coups might come out as salient episodes in the sources, but they should not obscure the more subdued and unexceptional character of daily bargains, compromises and negotiations.

Scholars of desert peripheries in the Middle East are often quick to announce that Bedouin, tribal or peasant voices cannot be retrieved, and that their worldviews are lost. These files contain hundreds of hand-written petitions penned by the tribesmen themselves, by sharecroppers unhappy with their shaykh’s taxation or by disgruntled exiled chieftains. They also consist of hundreds of proceedings of tribal councils held by both Bedouin and settled tribal elites.

The TCCDR appears in a new light here. The minutes of all these cases invalidate the blanket criticism formulated against the TCCDR by scholars of the British Empire. Undue fixation on the denunciation of the evils of colonialism has had the perverse effect of obliterating the extraordinary adaptive capacity of the Iraqi social fabric, regardless of the colonial-derived nature of its state legislation. In particular, the persistence of tribal modes of mediation operating along the same lines as in earlier times calls for a reinterpretation of the impact of state building.

Melisande Genat is a Stanford PhD student in the History department. She has been living and conducting research in Iraq since 2010. She focuses on interrelations between tribal, political and ethno-religious phenomena in the Iraqi Jazirah and the Sinjar region (1920-2020).

Carl Shook, Imperialist Invention or Uncertain Enterprise? Understanding British power through the political geography of Iraq

Among its many laudable effects, the critical turn in colonial studies of the 1970s and 1980s laid bare the myth of absolute colonial and imperial control. In particular, the rule of British governors, high commissioners, and advisors in Egypt, the Gulf, Mesopotamia, and Palestine throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were rightfully seen to rely on a host of indigenous interlocutors. In Mandate-era Iraq, urban elites and tribal shaykhs emerged as necessary vectors of imperial power, but who enjoying significant agency of their own. This suggested, rightfully so, that state-building was a complicated process involving multiple actors, interests, and possible outcomes.

However, we cannot discount the obvious power differential in Iraq between British military and mandate officials, on the one hand, and the Hashemite monarchy and tribal leadership on the other. This is clear in the process of delimiting, demarcating, and defending Iraq’s political boundaries in the 1920s and 1930s. The relative similitude of Iraq’s current form to the well-known Sykes-Picot Agreement, for example, or the ruler-straight lines drawn between Iraq and Nejd, during the 1922 negotiations with Ibn Saud, challenge us to reconcile current narratives of local agency with the historical fact of Britain’s ability to create incontrovertible, and permanent, facts on the ground.

This paper addresses this apparent incongruity by reviewing the last three decades of scholarship on the reach, limits, and form of British power in Iraq, then testing that literature’s conclusions against my own recent research on the origins and development of Iraq’s Arabian and Syrian boundaries, a process shaped, directly and indirectly, by the Bedouin tribes living in those borderlands. I conclude that by studying governance over local populations at the very sites where political authority was often weakest, we can better understand the role that coercive power played in Iraqi state-building and the literal shape of the new country.

Carl Shook is Lecturer of Islamic and Middle Eastern History at Loyola University Chicago. He received his doctorate in Modern Middle East History from the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago in 2018, and works on border-making and borderland populations of the Middle East.

Huma Gupta (MIT), The Architecture of Dispossession and State-Building in Iraq

This paper examines state-building in Iraq through the architectural production of the dispossessed. The dispossessed refers to cultivators from southeastern agricultural provinces like ʿAmarah that migrated to Baghdad and Basra in a mass exodus between 1920 and 1965. This great migration was a form of political practice akin to ‘voting with their feet’ that responded to conditions of debt, the ʿiqta tax farming system, rigid class hierarchies, coercion, and conscription. And, it resulted in the establishment of massive sarifa (reed and mud) neighborhoods in the capital, such as Asimah, Shakriya, and Washash that were often organized along kinship networks and built on occupied state-owned and private land. Migrants contributed to state-building by providing a supply of devalued ‘surplus’ labor for the army, civil service, construction industry, dairy production, domestic services, manufacturing, police, and transportation networks. The devaluation of their labor also accompanied a macroeconomic devaluation of migrant architectural production within a developmental state economy that was shifting from an agricultural to an oil-based economy in the 1950s that was more centralized and facilitated draconian policies of population control and political suppression. However, these neighborhoods posed a sustained economic, political, and territorial threat to the Hashemite and later, Republican regime along with their Anglo-American allies who became increasingly preoccupied with the ‘problem of the sarifa’ and the revolutionary potential of ‘sarifa-dwellers’ who were likened to the lumpenproletariat of pre-1789 France. Each successive regime tried to deal with this threat through alternating strategies of coercion, patronage, and propaganda. In order to financially and politically integrate rural migrants into the apparatus of the state, the dispossessed were offered a possession in the form of a house or a plot of land in peripheral settlements like Madinat at-Thawra and Al Shula in the 1960s. However, these solutions merely redesigned the architecture of dispossession that was previously marked by customary building materials to industrial forms of brick and concrete. This paper thus, argues that the intractable and intertwined ‘problems’ of the rural migrant and the slum are productive problems that stimulate capital accumulation through ‘solutions’ like architectural design, housing programs, urban planning, land grabbing, and large infrastructure projects. Yet, these problems merely function as a foil for the Iraqi state whose very model of economic development and political order was premised on an iterative process of dispossession.

Amir Taha, War and Insurgency in Southern Iraq: The Case Study of Shinafiyah, 1979-1991

Recent research on the state apparatus of the Baath regime under Saddam Hussein has provided us with empirically evidenced insights on the repression and cooptation of the Iraqi population. These valuable studies have not taken the geographic variation of the regime’s policies into consideration, such as Iraq’s urban-rural divide. Saddam’s administrative and political penetration of Iraqi villages depended on local social and tribal elites and tight-knit social ties, which created a power dynamic unlike the cities. This differing social context suggests that the Baathist coercion/co-optation model of the population was a much more complex and heterogeneous process than we originally concluded with regard to state control in Iraq. This paper is based on archival investigation and in-depth oral history research on the village of Shinafiyah, a district (nahiyah) in the southern province of Qadisiya, which saw extensive violence in the 1991 uprising and repression. It indicates that regime agents were just as embedded in the village community as ordinary citizens. Depending on the local conditions, coexistence with the Baathist regime was possible if local interests of the regime agents could contend with and overrule the regime’s overall interests. Contestation and cooperation in Iraq were not only a matter of politics but also a question of community and reputation. The paper concludes that the locals were aware of this matrix of power and acted accordingly when they saw opportunities to contest the regime and pursue their own interests.

Amir Taha is a Lecturer at Utrecht University’s Department of History. He has a background in the discipline of history, with a specific interest in social movements, state formation, and cultural representation. He has published, researched and lectured about the rise of paramilitarism in Iraq during his time at the Dutch institute for war holocaust and genocide studies (NIOD). Currently he is researching and teaching about the Baath regime in Iraq (1968-2003) conducting interviews with Iraqi witnesses and doing archival research.

Friday: 15.15-16.45 Panel 4: Beyond Sectarianism

Michael Degerald, Race in modern Iraqi History: Questioning the not-so-sectarian dimensions of social tensions

Is race useful as a concept in studying modern Iraqi history? Going by our existing studies, the resounding answer seems to be ‘no.’ Asked differently, is Iraq fundamentally different from other parts of the world where race is undoubtedly present? This paper draws on critical studies of race alongside modern Iraqi history to explore the necessity of race in our analyses. Existing concepts- especially sectarianism- have closed off the space for us to see the concept of race in Iraqi society. State discourse demonized opposition groups during the Iran-Iraq War by labeling them as شعوبية and expelling them discursively, and sometimes legally, from the Iraqi nation. My dissertation laid out how this amounted to a form of racialization, in which state power defined Iraqis into and out of the Arab nation. Those labeled as shu’ubiyyun were deemed “Persian,’ but other groups, especially Yazidis, were ‘Arabized’ in coordination with community leaders despite the lack of consensus that Yazidis are Arabs. By exploring the conceptual vagaries of both طائفية and عنصرية in the original Arabic, we can see that those two terms overlap and cannot be extricated from each other. Sectarianism is most commonly understood to refer to religious differences while racism often refers to ethnic differences like Arabs and Kurds, but this facile separation ignores the complex construction of all of these categories. While I argue that the racial category of شعوبية has not persisted in Iraq because it did not resonate with group identities held by those labeled with this slur, this work can hopefully be the beginning of better conceptual and temporal delineation that helps researchers identify if and when phenomena described as ‘sectarianism’ may indeed be better described conceptually as ‘race’ and ‘racism.’

Michael Degerald received his PhD from the University of Washington in December of 2018. He is currently a Guest Researcher at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Lund University in Sweden. His book manuscript, largely based on his dissertation, is tentatively titled Transforming Iraq. It is a media, cultural, and intellectual history of Iraq from 1968-1991. It will explore state cultural institutions and publications, mass literacy campaigns, expansion of public infrastructure, adoption of technology, and attempts to vivify Iraqi heritage, both before and during the war against Iran. In all of these facets, Michael reads the Iraqi experience alongside debates and politics in the project of the Third World, especially the Non-Aligned Movement of which Iraq played a measurable role. Michael also created a digital archive of Ba’thist texts he gathered during his dissertation research, and the link is listed on his twitter bio.

Christopher Cooper-Davies, Between sectarian populism and anti-sectarianism: mechanisms for Shi’i national integration in Hashemite Iraq

This paper analyses two Shi’i discourses which emerged following the institution of the Iraqi nation state, the rapid expansion of print media in the Middle East, and a new phase in Sunni – Shi’i relations. The first discourse was political and unique to Iraq. It saw Shi’i writers expressing their grievances with the current social, political and economic status-quo, by promoting a populist political programme for a more equitable national future. The second discourse developed in response to the deterioration of inter-sect relations and the new public exposure the Shi’i community was coming under in the modern era. It was less nationally specific, although Iraqi Arab intellectuals and ulama were its leading proponents, and it was overtly anti-sectarian, promoting a unified vision of Islam and an acceptable face of Shi’i tradition.

The paper highlights some of the key themes running through these distinct but overlapping discourses, which at times borrowed heavily from each other. The contradictions between the two were played out in the pages of the leading Shi’i journal of the early twentieth century, al-Irfan, as well as in the published works of Iraqi Shi’i intellectuals and ulama such as Muhammad Hussein Kashif al-Ghita and Abdul Razzaq al-Hasani. Analysis of this material highlights the intellectual and cultural struggle of the community as it grappled with the challenges of modernity and national integration.

By showing that Shi’i sectarian political identities were renewed, reinvented, contested and resisted during this period, the paper seeks to get beyond primordialist understandings of Shi’i sectarian mobilisation in Iraq. It shows that both the ostensibly sectarian discourse and its anti-sectarian counterpart should be seen within the rubric of what Ussama Makdisi has recently coined the ‘ecumenical frame’ for understanding the development of the Middle East nation state system. Both discourses also signified a fundamental reconceptualisation of what Shi’ism meant for those inside and outside of the faith.

Christopher Cooper-Davies is a PhD student at the University of Cambridge, researching the political and cultural history of the Shi’i community in Iraq during the early twentieth century. Before beginning his PhD, he studied at SOAS and Queen Mary, University of London.

Joseph Kotinsly, The Politics of Suffering: An examination of the Iraqi Shi’i Opposition Movement’s response to the 1991 March Uprisings

Following the 1991 March uprisings, the Iraqi government launched a series of military campaigns in the country’s southern marshlands. While contemporary accounts maintain that the state’s actions were driven by sectarian animosity towards Iraqi Shi‘is for their purported role in fomenting the uprisings, recent scholarship counters this narrative by elucidating the universal suffering of all Iraqis throughout the 1990s, and challenging claims that the southern uprisings were an exclusively Shi‘i revolt.

This study seeks to contribute to this discourse by delineating the critical role played by various Iraqi Shi‘i opposition groups, namely, the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI) and the Iraqi Da‘wa Party, in propagating sectarian coded narratives of the state’s actions in southern Iraq. By demonstrating how these organizations strove to imbue the southern uprisings with Shi‘i-specific symbolism and depict the government’s response as sectarian fueled reprisals aimed to collectively punish Iraqi Shi‘is, this study also highlights a distinct shift in SCIRI and Da‘wa’s political messaging. Whereas SCIRI and Da‘wa’s publications during the Iran-Iraq War emphasized that their respective brands of Islamic government would be representative of all Iraqis, following the war’s conclusion these organizations strove to portray themselves the primary defenders of Shi‘i interests in Iraq and focused near exclusively on the need to protect the rights of Iraqi Shi‘is. Consequently, this study will also identify the changing political and social contexts that can account for SCIRI and Da‘wa’s shift away from language of Islamic universalism towards a more overt Shi‘i-centric discourse. Beyond its historiographical contributions vis-à-vis the 1991 March Uprisings, by demonstrating the contingency of SCIRI and Da‘wa’s deployment of Shi‘i-centric rhetoric, this paper also challenges the explanatory power of primordialist narratives concerning the salience of sectarian identity in Iraqi state and society.

Joe Kotinsly is currently a second year PhD Student in the Department of Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas. Prior to attending UT Austin, Joe received his MA from Tel Aviv University and spent a year at the American University of Beirut conducting research for his Master’s thesis on the history of the Iraqi opposition movement. His current research focuses on discourses of Shi’i persecution in Bath’i Iraq.

Jinan Al-Habbal, The Evolution of the Iraqi Army

This paper examines power-sharing mechanisms and political leaders’ instrumentalization of ethnosectarian identities in Iraq’s military. It explores how sectarian identities have evolved in the Iraqi Army throughout history and whether a national army can be built in a divided society. The paper traces the formation of the military during the Ottoman period and the British Mandate and the British influence on the army’s structure after Iraq’s independence. The paper then focuses on the post-independence period and the military coups that ultimately led to the Ba‘thist regime, which suppressed the military and created parallel security forces dominated by the Sunni minority. Following the 2003 U.S.-invasion of Iraq, the United States disarmed Saddam’s Army and implemented power-sharing mechanisms. Iraq’s liberal consociationalism does not officially specify the sects of senior military posts, allowing ethnosectarian groups to enroll based on their demographic representation. However, de-Ba‘thification has alienated Sunnis and weakened the military. Former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki abused his powers and established several security institutions without any regulation. Moreover, leaders have politicized the army’s recruitment process and assigned their clientelist followers to senior posts. The presence of sectarian militant groups has also hindered the formation of a national army and limited Iraq’s legitimate monopoly on the means of violence. The U.S. troops’ withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 left behind a weak military unable to deal with terrorism and sectarian divisions. Thus, Iraqi citizens relied on the sectarian Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) to fight Da‘esh following the army’s disintegration in 2014. The paper concludes that power sharing has entrenched sectarian identities in the Iraqi military and impeded a national army that reduces fragmentations.

Jinan Al-Habbal is a Researcher at the Conflict and Civil Society Research Unit at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). She is part of the team working on a project entitled “Legitimacy and Citizenship in the Arab World,” funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Jinan holds a PhD in International Relations from the University of St Andrews. Her research examined the impact of political leaders and sectarian power-sharing state institutions on hindering democracy in Lebanon and Iraq. She is the co-author of The Politics of Sectarianism in Postwar Lebanon.

Friday: 17.00-18.30 Keynote Panel

Orit Bashkin is a historian who works on the intellectual, social and cultural history of the modern Middle East. She got her Ph.D. from Princeton University (2004), writing a thesis on Iraqi intellectual history and a BA (1995) and MA (1999) from Tel Aviv University. Since graduation, she taught modern Middle Eastern history in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago. Her publications deal with Iraqi history, the history of Iraqi Jews, the Arab cultural revival movement (the nahda) in the late 19th century, and the connections between modern Arab history and Arabic literature. Her graduate students explore the cultural history of Iraq, the British mandates in Trans Jordan and Iraq, leisure in the Arab world, Mizrahi women, and Arab political thought. At the University of Chicago, she teach classes on nationalism, colonialism and postcolonialism in the Middle East, on modern Islamic civilization, and on Israel-Palestine history.

Dina Rizk Khoury is a John Simon Guggenheim and American Council of Learned Societies Fellow. Her research and writing spans the early modern and modern history of the Middle East. Her first book, State and Provincial Society in the Ottoman Empire: Mosul, 1540-1834, won awards from the Turkish Studies Association and British Society of Middle Eastern Studies. Her second book, Iraq in Wartime: Soldiering, Martyrdom and Remembrance draws on government documents and interviews to argue that war was a form of everyday bureaucratic governance that transformed the manner in which Iraqis made claims to citizenship and expressed notions of selfhood. She is currently working on a book on labor migration and the birth documentation regimes in the northern Persian Gulf between the 1880s and 1930s.

Sara Pursley is Assistant Professor in the departments of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies and of History at New York University. She is the author of Familiar Futures: Time, Selfhood, and Sovereignty in Iraq (Stanford, 2019) and numerous articles, including “‘Ali al-Wardi and the Miracles of the Unconscious,” in Psychoanalysis & History. From 2009-2014 she served as associate editor of the International Journal of Middle East Studies.

Eric Davis, Ph.D. Chicago, is Professor of Political Science, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA. Davis is the author of Challenging Colonialism: Bank Misr and Egyptian Industrialization, 1920- 1941, which was recently reissued by Princeton University Press in its Legacy Series (Arabic translations: Institute for Arab Studies, Beirut; Dar al-Sharook, Cairo), Memories of State: Politics, History and Collective Identity in Modern Iraq (University of California Press; Arabic translation: Arab Institute for Research and Publications, Beirut and Amman), and Statecraft in the Middle East: Oil. Historical Memory and Popular Culture. He has a contract with Cambridge University Press for Taking Democracy Seriously in Iraq, and is currently completing a study, Youth and the Allure if Terrorism: Identity, Recruitment, Political Economy.

Davis has held fellowships from the Shelby Cullum Davis Center for Historical Studies, Princeton University, the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin (Institute for Advanced Studies), the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, the United States Institute of Peace, the IREX Foundation, and the Social Science Research Council, where he led a five-year study of political and social change in Arab oil-producing countries. In 2007-2008, he was appointed a Carnegie Scholar by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Davis lectures regularly at the US Department of State where he assists in the training of diplomats and other US government personnel serving in Iraq. He founding director of the MA Program in Political Science – United Nations and Global Policy Studies (UNMA), Rutgers University, and lead scholar in a project sponsored by the UNMA, the Rutgers University Honors College and the American University of Sharjah, Youth, Social Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development. This project recently received a grant to hold a workshop for youth social entrepreneurs at the Hollings Center for International Dialogue in Istanbul. Davis is a member of the faculty of the Master’s Program in Business and Science, Department of Electrical Engineering, Rutgers University, and a member of the Executive Committees of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies and the Center for European Studies, also at Rutgers University. He is fluent in Arabic, German, Italian and French.

His research interests include democratic theory, the relationship between historical memory and state power, the political economy of development, and the comparative politics of the Middle East. Davis is the author of the blog, The New Middle East

Saturday: 10.00-11.30 Panel 5: State Power and Natural Resource Development

Dale Stahl, The Third River: Oil, Water, and the Iraqi Development Board

The Iraqi government established a Development Board in 1950 to direct growing revenues from oil exploitation toward agricultural and industrial development projects. The Board designated the vast oil supplies in Iraq’s north and south as the country’s “Third River,” as vital to Iraq’s livelihood as its other two waterways, the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Over the course of the 1950s, the Board allocated much of the revenue from Iraq’s “Third River” to modifying the environment of its other two rivers, emphasizing flood control, irrigation, and the production of hydroelectric power. Thus, the Development Board functioned as a sociopolitical institution for transforming, connecting, and directing an increasingly complex arrangement of flows. Unlike Iraq’s other two rivers, a good portion of the “Third River” flowed west through pipelines to the Mediterranean Sea. Oil revenue flowed back through the Iraq Petroleum Company to the Baghdad government. The Board transformed that revenue into flood control and irrigation projects that depended on transnational networks of technical and financial expertise. Once deployed, this expertise helped produce infrastructure to capture, harness, and direct the flow of water, which was used frequently to produce electricity or agricultural commodities. This paper, part of a larger environmental history of the Tigris-Euphrates River Basin, examines the Development Board’s work through the stories of three human actors: Ahmed Sousa, an Iraqi irrigation engineer; Michael Ionides, the British advisor to the Development Board; and Arthur Salter, the former League of Nations official brought by the Development Board to Iraq to complete a comprehensive development plan. In doing so, the research seeks to situate Iraqi “development” in relation to other modernization schemes in the Middle East at this time, while also suggesting the role energy and environment may have played in the 1958 military coup that brought an end to direct British involvement in Iraqi affairs.

Tiffany Floyd, The Rivers of Time: Deep Time, Petromodernity and Iraqi Modern Art in Al Amiloun Fil Naft

This paper seeks to understand the cultural context of the Iraq Petroleum Company’s house magazine Al Amiloon Fil Naft (Oil Workers – al-‘Amilūn fi’l-Nafṭ), produced in Baghdad of the 1960s. This decade witnessed a striving, energetic artistic community in Iraq that benefited from the oil revenues of an industry in crisis and transition. Within this context, the entities of oil and art, corresponding to the contingencies of geology and archaeology, sought a common prize that can be characterized as an ideological desire to associate with the deep past, a past that promised riches and glory in the literal and figurative pits of the earth. Utilizing the tool of ‘deep time,’ the present study aims to demonstrate that the content of Al Amiloon Fil Naft was tethered to larger ideological formations of temporality. More than just an intellectual resource, the ‘past’ was activated as a vital mechanism in cultural production, a project that harnessed a distant antiquity to stake a claim on the contemporary moment. This project was shared by agents of oil and art alike as both drew bonds of kinship and continuity with an abstract ancestor for differing purposes. The crossing and overlapping tracks of art, oil, and history created a complex stratigraphy in Iraq during the 1960s. This paper examines an unlikely cultural publication in relation to the forces of petromodernity and ‘deep time’ discourses in order to map this stratification.

Tiffany Floyd is a PhD candidate at Columbia University specializing in twentieth-century Iraqi art. Her current dissertation is focused on the relationship between Iraqi modern art and the country’s rich antique past; thus, her primary research interests include the politics of archaeology and time, the construction of modern artistic and intellectual identity in Iraq, and the deconstruction of the complex modernist category of “Mesopotamia.” Her other interests center on the history of photography, postcolonial theory, modes of affective reception and the destruction of Iraq’s cultural heritage. Tiffany has worked on several important projects including the Mathaf Encyclopedia of Modern Art and the Arab World, the Modern Art Iraq Archive, and the current Getty-funded project Mapping Art Histories in the Arab World, Iran, and Turkey.

Isacar Bolaños, The French Connection: Informal Empire, Environmental Management, and Foreign Technocrats in Hamidian Iraq

Britain’s informal empire in late Ottoman Iraq is well known, as are the means that facilitated it, most notably steamship technology. Less studied have been French efforts to have greater influence in late Ottoman Iraq by means of French technical expertise in the field of hydraulic engineering and the circumstances that facilitated those efforts – Abdülhamid II’s vast land acquisitions in central and southern Iraq for the purposes of exploiting the region’s agrarian potential and water resources. This paper examines this episode in the history of late Ottoman Iraq to provide insights into both France’s informal empire in Ottoman Iraq and the growing presence of the emerging Ottoman technocratic state in the empire’s Arab frontier regions.

Isacar A. Bolaños works on the environmental history of the Ottoman Empire. His current book projects explores how floods, epidemics, and famines shaped Ottoman statecraft in Iraq during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He has recently published an article on this subject in the International Journal of Middle East Studies. In the Fall, he will join the faculty of the Department of History at California State University, Long Beach, where he will offer courses on world history, environmental history, and Middle East history.

Şehnaz İyibaş, Irrigation in the Late Ottoman Iraq: The Hindiya Barrage 1890-1914

This study investigates the role of irrigation practices in the Ottoman centralization attempts in Iraq between 1890 and 1914. By “role,” it means the ways in which the irrigation infrastructures were used in accordance with the Ottoman political and economic interests in the Iraqi provinces. In doing so, the research focuses on the Hindiya Barrage which was one of the largest-scale irrigation projects in Ottoman Iraq in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The study examines the Barrage depending basically on the Ottoman state archives including the local petitions and the memoirs of the Ottoman-Iraqi officials in order to trace the dynamics of center-periphery and state-society relationships. Moreover, the study aims to question how the water resources are organized by the Ottoman imperial center through the construction of the Hindiya Barrage. In retrospect, it appears that the possibilities of an Ottoman power consolidation in Iraq was constantly being undermined by political and financial shortcomings in addition to the rising imperial ambitions of the British government in the region. The repair of the Barrage in 1913 under the British financial and technical support paved the way for further political interference of the British, a process which ended up with the demise of the Ottoman rule in Iraq and the official declaration of the Iraqi mandate. Given the fact that this course of events was unexpected and historically contingent at the time, examining such a wide-scale irrigation project would allow us to better evaluate the ways in which a multiethnic, multi-linguistic, and multi-religious polity sought to achieve a renewed territorial integration with its provinces in order to comply with a nation-state dominated world conjuncture.

Şehnaz İyibaş is currently an MA student at Koç University, İstanbul. She is also a research fellow of the UrbanOccupationsOETR project at the same university. Her research interests focus on the political, social and cultural history of the Arab provinces in late Ottoman Empire.

Saturday: 11.45-13.15 Panel 6: Formation of Iraqi Identities and Social Classes

Hala Fattah (Independent Scholar), The Invisible Iraqis: Georgian, Daghistani and Circassian Families in Early Twentieth Century Iraq

From the mid-eighteenth to the mid- twentieth centuries, several North Caucasian communities took root in Iraq. Whether because they arrived in the country as a result of conquest or post-conquest circumstances, these unwilling/willing migrants settled in Iraq and have served the country faithfully until the present day. The questions posed in this paper is why these migrant communities chose to seemingly assimilate without any visible difficulties in Iraq when other communities from the North Caucasus (Circassians in Jordan, for instance) saw themselves as separate from local populations and the political pressures these represented. In a country seemingly so riven by internal divisions, why did the Georgian, Daghistani and Circassian communities almost instantly identify with Iraq and become one of its chief defenders? This paper will look at the elite background and marriage patterns of two great North Caucasian families— the Sulaimans and the Daghistanis—to arrive at a tentative conclusion on the adaptability and absorptive capacity of these communities in Iraq.

Pelle Valentin Olsen, Iraqi Jews and the Consumption and Production of Leisure: The Case of Iraqi Cinema

In the 1910s and 1920s, when cinema spread globally, the novel commodity and forms of representation that it offered changed the structure of leisure, entertainment, and modern life itself. Iraq did not become part of the modernity of cinema leisure belatedly. During the 1920s and 1930s, cinemas began to appear across Iraq. Like in other urban centers globally and across the region, in Iraq, the cinema is as a prime example of a uniquely modern form of leisure that quickly became one of the most popular and widespread forms of mass entertainment for a large number of Iraqis.

This paper contends that it is not possible to understand Iraqi modernity without paying close attention to the cinema, the images it projected, and the ways in which it began to structure and divide Iraqi leisure and time in new and different ways. This entails examining the ways in which the cinema was a form of leisure in which Iraqi Jews not only took part on all levels, but in which they played a pioneering and dominant role right from the inception of Iraq’s cinema industry. This paper traces the beginnings of the cinema industry in Iraq and argues that Iraqi cinema culture was fundamentally transregional and global. As cinemagoing became a habit, cultural products, performers, and people with technical skills came to Iraqi from Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, India, Europe, and North America. Cinema, as this chapter will show, is therefore an elucidating example of how transregional and global products, knowledge, and knowhow was localized. However, while Iraqi minorities, particularly Jews, played a dominant role in first decades of Iraqi cinema, this chapter complicates sectarian-based approaches to the landscape of leisure in Iraq, illustrating the heterogeneous nature of the lived spaces of the city and even the imagined space of the nation. In other words, the cinema was a space in which Iraqis, regardless of religion, gathered to be entertained, transported, and thrilled by the magic of the screen.

Pelle Valentin Olsen joined the University of Chicago as a PhD student in 2014. He holds degrees from the University of Oxford and the University of Copenhagen. Pelle is interested in the history of leisure, education, gender, and sexuality in Hashemite Iraq.

Andrew Alger, Hakeems for Whom? Hospital and Clinical Practices in Baghdad, 1917 – 1957

My paper seeks to better understand what, in the case of twentieth-century Baghdad, the institutionalization of medical care in hospitals and clinics contributed to the social production of urban space. The contest over urban space characterizes much of Iraqi politics in the twentieth century, with street demonstrations and migration from the countryside regularly invoked to explain ideological trends and the consequences of particular cultural and infrastructural achievements. Medicine has only recently entered this discussion in the work of Omar Dewachi and Sara Farhan. Building on these foundations, my paper reads Arabic and English sources, ranging from public health records to doctors’ memoirs, as evidence that medicine in Iraq was unthinkable apart from the politics of neighborhood development.

Over the course of British occupation and the Iraqi monarchy, hospitals and medical clinics wove new practices of healthcare into a patchwork of emerging and established neighborhoods in Baghdad. Medical clinics set up by British public health officers drew thousands in for the treatment of eye diseases and inoculations, employing local and foreign health practitioners to do so. Hospitals, in contrast, operated mainly by restricting access to curative medicine, reserving lab tests, surgery, and a doctor’s diagnosis for a few. This restrictive function arose from the widespread assumption that hospitals needed to serve the national population as a whole, doing their part to manage the flow of people into and through the city, and so needed to evaluate patient’s physical mobility and economic potential. Fundamental differences between hospital and clinic accentuated existing class cleavages throughout the city and extended them further to the places where the city was growing. By the start of the republican era, the urban poor had accustomed themselves to an understanding of healthcare defined by prevention, while the patients occupying beds in specialized hospitals were from the middle classes.

Andrew Alger is finishing his Ph.D. in history at the CUNY Graduate Center. His dissertation is entitled “Building Baghdad: The Construction of Urban Space, 1921 – 1963.” He is the recent recipient of a research grant from The Academic Research Institute in Iraq and a candidate for the 2020 MESA Nominating Committee student member.

Saturday: 14.00-15.30 Panel 7: Beyond the Nation: Iraq in Global Perspective

Esmat Elhalaby, India in Iraq/Iraq in India

Through histories pilgrimage, trade, and translation, Iraq has been tied to India for many centuries. Its cuisine and slang most readily reveal their connection to the contemporary observer. In the colonial period, especially during the British conquest of Iraq by Indian arms during the First World War and its aftermath, this relationship was indelibly reconfigured. Through an examination of the Iraqi and Indian press, the British colonial record, and travelogues written by Indians to Iraq before and after the British occupation, this paper aims to highlight the depth of the Iraqi entanglement with India and vice versa. I aim to examine three themes in particular. First, and at the most basic level, how Iraq and the British occupation of Iraq was perceived by Indian observers. Second, more specifically, how Iraqi space and history gets compared and at times subsumed into the South Asian past by Indian writers. And finally, I offer a glimpse into the social history of Indians in British and Hashemite Iraq.

Esmat Elhalaby is currently a Humanities Research Fellow at NYU Abu Dhabi. He received his Ph.D in history from Rice University in 2019. His book project, Parting Gifts of Empire: Palestine, India, and the Making of the Global South, is an intellectual history of West and South Asian interaction from the decades before the twin partitions of 1947/48 until the days of Non-Alignment.

Noga Efrati, Revisiting Early Women’s Activism in Iraq: a Transnational Perspective

The study of women’s history in Iraq is still in its infancy. Unlike in neighboring countries, historians of women’s early political and feminist activism are still engaged in fundamental tasks identified, already in the 1970s, as essential for constructing women as historical subjects. Moreover, central common developments characteristic of early women’s movements in the Middle East – such as women’s participation in the intellectual debate on their position in the family and society, the establishment of a myriad of women’s organizations, evolution of a women’s press, and women’s involvement in anticolonial struggles – still await an in-depth study.

Efforts to overcome these lacunae however, are leading toward a narrow nation-centered historical writing which tends to detach women’s activities from regional and global processes, social networks and exchanges. My paper will stress the utility of placing early women’s activism in Iraq on the backdrop of wider historical developments such as the “first modern globalization” with its unprecedented intensification in the movement of people, technologies and ideas, the spread of colonialism and nationalism, and the evolution of global and regional feminism.

Focusing on the emergence in 1923 of “Nadi al-Nahda al-Nisa’iyya”, the first Iraqi women’s organization, I will demonstrate how such a transnational perspective helps shed more light not only on the evolution of local women’s activism but on regional and global women’s activism as well.

Noga Efrati is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of History, Philosophy, and Judaic Studies at the Open University of Israel. A historian of the Middle East, her research focuses on women and gender and on the social, legal, and political history of Iraq. Between 2006 and 2011 she headed the Post-Saddam Iraq Research Group at the Harry S. Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. She is the author of Women in Iraq: Past Meets Present (Columbia University Press, 2012), and of many articles concerning women’s rights activism in Iraq. She is also the co-editor with Amnon Cohen of Post-Saddam Iraq: New Realities, Old Identities, Changing Patterns.

Hilary Falb Kalisman, Global Iraq: Gender, Education and Travel

In the late 1930s, Salwa Nassar, a Lebanese-born graduate of the American University of Beirut and by the 1940s the Arab World’s first female PhD in physics, traveled to Iraq as a teacher. During the 1930s essentially all of Iraq’s dozens of female secondary school teachers had, like Nassar, journeyed from their homes outside Iraq. Despite her trailblazing path to academia, Nassar asserted that her gender proved a non-issue in her work in physics because there were so few qualified individuals in the region. She claimed that in the Arab World, “There is no set tradition against women in science and not much competition, either from men or women.” Yet, Nassar told her students that “her success was nothing compared to a baby in her arms,” thereby emphasizing women’s place within the home and family. Nassar, like so many of her less-well known contemporaries, lived a contradiction. The educational profession coded masculine, demanding that academics and teachers travel, thereby becoming part of global, and globalizing, intellectual currents. However, female educators’ gender was automatically connected to domestic life.

This paper breaks with nationalist conventions that have defined the study of Iraq by reframing the country as an international hub of education. By examining the journeys of Iraq’s female educators, this paper broadens our understanding of gender and globalization. Analyses of globalization have linked women with domesticity, and men with economics and travel, thereby distorting our understanding of these processes. Reckoning with the impact of gendered understandings of the local, national and global, this paper argues that female teachers in Iraq suffered through the disjuncture between these gendered expectations, but also expanded them by forcing new transnational pathways. Women’s travels, that Iraq’s Ministry of Education so reluctantly facilitated, helped solidify Iraq’s place as a regional center, within the broader Middle East.

Hilary Falb Kalisman is an Assistant Professor of History and Endowed Professor of Israel/Palestine Studies in the Program for Jewish Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder. This year she is an American Council of Learned Societies Fellow, a National Academy of Education Spencer Postdoctoral Fellow, and a non-resident fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School. Her research focuses on education and politics in Iraq, Jordan, Palestine and Israel.

Kate Tietzen, Iraqis in Russia: The Organizations of Iraqis Outside the Region-Moscow, 1988-1994

This paper explores the role of the Organizations of Iraqis Outside the Region (OIR) in Moscow after the fall of the USSR. It also examines the influence and power of the Ba’thist party beyond the borders of Iraq. OIRs, essentially a foreign extension of the Ba’thist apparatus, often run out of the respective Iraqi embassies, conducted political operations for the Ba’thist party abroad, including surveillance and intelligence campaigns against entities and persons of interest, both foreign and domestic. Operations were conducted on members of the Iraqi diaspora as well. The OIRs were critically important for the powers at be in Baghdad, and with the Iran-Iraq War and Saddam’s policies forcing more Iraqis to emigrate, an examination of the OIRs show “how migration pushed the regime to transform the party into a transnational actor, rather than a purely domestic entity,” as argued by Samuel Helfont in his 2018 article, “Authoritarianism Beyond Borders: The Iraqi Ba’th Party as a Transnational Actor.”

This paper argues that despite the chaos of 1991—the First Gulf War and the collapse of the Soviet regime— OIR Moscow continued to run political and diplomatic operations as it did the Cold War. The difference now, however, was that its mission was even more important than before. The new Russian Federation was a key part of Iraq’s plan to contest American-led sanctions following the First Gulf War. Tasked with cultivating relationships with pro-Iraqi entities in Russia, OIR Moscow carried out numerous operations to court soft-power targets, including new political factions, media groups, civil societies, and old Soviet allies. However, this is not to say that all operations ran out of OIR Moscow were without problems. Personnel issues within the embassy and tensions with Russian authorities often forestalled or even prevented the results Baghdad so desperately sought.

Kate Tietzen holds a PhD in History from Kansas State University. Her dissertation used Iraqi Ba’athist documents housed in the United States to analyze the Iraqi-Soviet diplomatic and military relationship during the Cold War and beyond the fall of the Soviet Union. She has studied Arabic in Oman and Jordan; the latter was part of a U.S. State Department Critical Language Scholarship. She received a Smith Richardson Foundation World Politics and Statecraft Dissertation Fellowship and The Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations Michael J. Hogan Foreign Language Fellowship in 2018. She was a research fellow for the U.S. Army’s Operation IRAQI FREEDOM Study Group in 2015. Kate graduated from University of Wisconsin-Madison with her BA in History and Political Science, and Clemson University with her MA in History.